A buddy-system blog of film reviews. Inspired by E.M. Forster's rhetorical question: "How do I know what I think until I see what I say?" Please let me know if you'd like to take a stab at writing a review. (I've been told that the experience is a combination of mass frustration and deep satisfaction.) I will watch anything! Bring it on...

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

Of Buddies and Beasts

My original buddy, Brian, is back for this one and hopefully many more. We knew pretty little about Beasts of the Southern Wild going in, which meant for that much more to delightfully stumble upon. Enjoy!

Brian's Review of Beasts of the Southern Wild

Beasts of the Southern wild is wonderfully strange and ambitious.

It's odd then to write about the film's influences. It can even look like avoiding a difficult film. Yet, watching it, I couldn't shake the sense that this movie was consciously setting itself in relation with two of contemporary cinema's most idiosyncratic and philosophical filmmakers: Terrence Malick and Werner Herzog. What's more, the film's final act seemed to offer an alternative vision of the world. So in a clumsy way, here is what I'm thinking about (still) in response to this movie.

First Malick, the more overt influence. In Beasts as in Days of Heaven, a young girl with a nearly incomprehensible accent narrates in voice-over a tale of adult relationships. Her voice is naive but philosophical. By narrating a story that is beyond her, she makes the relationships less familiar, more visible, and she comes of age. Stylistically, Malick's influence is strong: the subjective camera that parallels the child's point-of-view while maintaining one of its own; the lyricism of the imagery; the interest in natural landscapes; all of these are emblematic of Malick's recent films. The allegorical side-story of the prehistoric animals and the numerous handheld, shallow-focus close-ups could have come directly The Tree of Life. However, Beasts is very different from Malick's films in that it is less abstract, less sure that things will work out, less certain that God (of some sort) is in his heaven and all is well.

Second Herzog, a set of references that are more specific and less overt. In fact, I've wondered if they are there at all. But the more I think about them, the more I'm convinced that the final scenes of Aguirre: The Wrath of God are the proper context for thinking about the muddy, boat-centered lives of the people of the Bathtub. The only thing missing is monkeys. If you aren't sure what I'm referring to (or know and think I've lost it) watch this clip and this one.

I take the visual references to be plain. So the question becomes how Beasts' ideas about human life in a savage environment compare to those of Herzog's. It seems to me that Beasts flips the moral and ethical terms of Herzog's film on its head. Aguirre is mad, powerhungry and, despite all evidence to the contrary, confident of his superiority to the natural world. His death reveals his folly. In Beasts, the people on the boat are humble, generous and aim to live happily within the natural world. Their lives reveal an odd wisdom. The modern Aguirres (and they have become legion) live behind the levee, a concrete wall that pins nature in and drowns it. If Aguirre speaks to the danger of reaching impossibly high, Beast tells of the danger of sitting quietly in the world (but outside the system).

In the final act, I think the film leaves these sources behind and offers a very different and very old vision of the human condition. Here the concrete, unabstracted poor (who we see so little in contemporary film) live in a different world. Their lives are confusing because they are not presented as failed immitations of our own lives or as interestingly different lives that enrich our experience. They live lives that respond to, reject and denounce the sterile and, yes, lifeless choices we make every day. They are kings of their own kingdom, live their own lives. And life is a holiday. In short, they are carnival figures celebrating the return of physical life, nature, eating, drinking, sex, community, all the things we pretend we can buy at a market but can't. This vision is neither as complacent as Malick's nor as bleak as Herzog's, but it is no less philosophical and no less challenging. What it shares with these other films, however--and this is troubling, really troubling--is an oddly medieval anti-modernism.

As I left the cinema, these were the pieces of thoughts I had floating around in my head. They don't cohere much more now than they did then. But they interest me and hint at what makes this move one of the most exciting and smartest American movie I've seen in quite awhile.

Caitlin's Review of Beasts of the Southern Wild

by Caitlin Murphy

Thursday, July 26, 2012

New (England) Found Passion

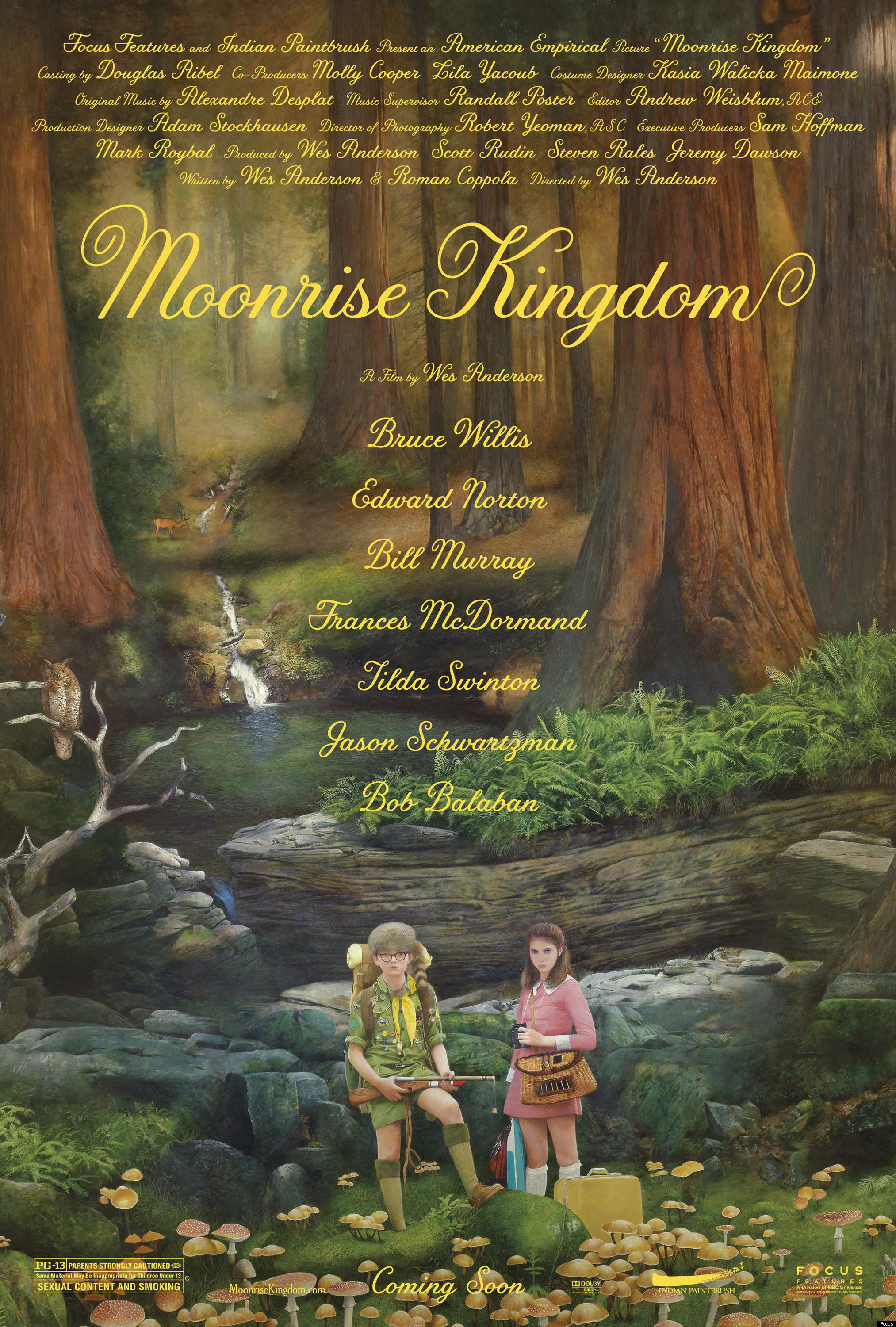

Joel's Review of Moonrise Kingdom

Caitlin's Review of Moonrise Kingdom

by Caitlin Murphy

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

Absence and Hunger

Caitlin's Review of Hunger Games

by Caitlin Murphy

I had made a vague, but deeply felt decision about The Hunger Games before I even walked into thetheatre. Something about hating it. My conclusion was based on a few previews, but also my sad suspicion that Jennifer Lawrence – who I’d adored in last year’s stirring film Winter’s Bone – was about to cash in her chips in yet another hyped-up book-to-blockbuster orgy.

Monday, March 5, 2012

Down, Down, Down

Sarah's Review of The Descendants

Caitlins Review of The Descendants

a review by Caitlin Murphy

Monday, February 13, 2012

A 20th Review

Enjoy our takes on David Cronenberg's latest offering...

(Oh yes, and as per the heading, this is also the 20th film reviewed on this blog, which launched last February 6th.)

Ken's Review of A Dangerous Method

Caitlin's Review of A Dangerous Method

by Caitlin Murphy

Monday, February 6, 2012

Walk the Talk

Enjoy our very different takes on The Artist...

Rip's Review of The Artist

a review by Jason Rip

Caitlin's Review of The Artist

a review by Caitlin Murphy

Tuesday, January 17, 2012

Me, You and Marilyn

Patsy's Review of My Week with Marilyn

As Cait mentions in her previous review, biography films are difficult to pull off. My Week With Marilyn, however, seems to rise to the challenge. Perhaps the difference is that it is an autobiographical story, which allows the audience to make more than a few concessions. The origins of this film had me pondering for many hours as to how the story, in its final presentation, came to be. On the surface, it's based on the experience of Colin Clark when he worked on the film, The Prince and the Showgirl, with Laurence Olivier and Marilyn Monroe. One can forgive any biases presented; any aspects of the characters that seem to be skewed, when taking into account the story is being told as seen through the eyes of a 23 year old film school graduate, working on his first major motion picture. But then, I pondered further. This story is more than just that as seen through the eyes of a 23 year old male at his first job. How much do you remember about your first job? Of course, you'd remember much more if it was working with Marilyn Monroe! And you kept a diary. I was cynical about the diary a little bit. I would imagine that in the years between his journaling and the publishing of the two journals this film is based on, Mr. Clark did a bit of polishing and editing. So, it's safe to assume that this story, in final presentation, is told through the eyes of a 23 year old film school graduate, as he recollected from his journals, published much later. Are you still with me? All that to explain why I find this film to be believable, more so than other films about real people. I was able to buy into it. It must also be much easier to account for a week of someone's life, rather than their entire life. The audience was allowed to bring their own preconceived ideas about the characters into the story. And there are a lot of preconceived notions about Marilyn Monroe.

Caitlin's Review of My Week with Marilyn

by Caitlin Murphy