A buddy-system blog of film reviews. Inspired by E.M. Forster's rhetorical question: "How do I know what I think until I see what I say?" Please let me know if you'd like to take a stab at writing a review. (I've been told that the experience is a combination of mass frustration and deep satisfaction.) I will watch anything! Bring it on...

Sunday, January 27, 2013

The More Things Change

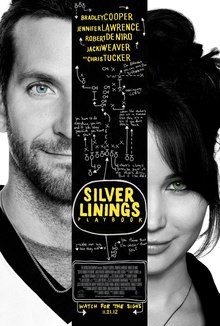

Somehow, nearly 5 months have elapsed since the last reviews. Shameful. But as my original blog-buddy Brian and I discovered as we began our Oscar nom viewing checklist, there is always a ridiculously contrived and unsatisfying upside to every down. Sigh. Enjoy these dismissals of Silver Linings Playbook.

Brian's Review of Silver Linings Playbook

Genre in Bad Faith

by Brian Crane

So I wasn't going to watch Silver

Linings Playbook. I'd seen the trailer and was pretty sure that it would be

terrible. Then one day, I found myself heading to a theatre to watch this thing

with Caitlin as part of our Best Picture screening list. Sitting down, I was

genuinely confused: how could a trailer be so misleading? I quickly learned, it

wasn't.

This movie is clearly a romantic

comedy. But in what I take to be a bid for contemporaneity or seriousness, it

makes a big deal about cutting through the bull, getting real, and addressing

the problems of relationships today. The hard truth this film proposes is that a

lot of us are sick, diagnosable, requiring accommodation. To know each other,

the characters don't need to communicate. They just need to be brought up to

speed on their case histories. And so, in scene after bathetic scene, we listen

to unpleasant characters announce their diagnoses to each other as if these

constituted personalities. "I AM" he says. "I AM" she says. "I AM" he says. And

so on and so on. And who cares?

For all it's self-importance, this

approach to character is much more simplistic than the approach native to

romantic comedies of the classic 1930s sort. Watch Bringing Up Baby or

The Philadelphia Story or It Happened One Night and you'll see

movies about adults made for adults. They have happy endings, yes. But these

movies earn those endings in complicated and emotionally complex stories that

transform their characters and launch them forward into life. Nothing in

romantic comedy--the cinematic genre most closely related to the theatre of

Shakespeare--is simple or easy. It only seems that way because we want so badly

for its faith in us to be true.

Silver Linings Playbook may

believe its view of humanity is smarter and truer than romantic comedy's, but in

the end, it can't pull off the picture it wants to paint. "I AM" plus "I AM"

doesn't equal "we." And so in it's final moments, the movie generates the

romantic closure it seeks by embracing (without avowing) the romantic genre it

has worked so hard to repudiate. Out of the blue, this movie about him saying "I

AM sick, that's just me," and her saying "I AM (not) a slut, deal with it,"

becomes a movie about a dance competition, one part Strictly Ballroom,

one part Little Miss Sunshine. Untrained, outclassed and with all of the

family's fortunes on the line (don't ask), the characters decide to try their

best, dance their hardest, and in the end, against all odds, discover they can

do it if they just let go and have fun. The family fortune is saved, and the

two, now lovers, find each other and kiss in the empty nighttime streets, happy

finally together.

I think this movie wants to update a

genre. It wants to make those silly, old-fashioned movies take account of what

we "know" today about human experience. How after all, if so much of what we

feel and experience is actually symptomatic of illness, can you find love? It is

telling (and reassuring) that the movie can't offer an answer any different than

the established generic answer. That four-hundred year old tale of marriage

delayed but achieved through work and conversation still rings true to our

experience and aspirations. The tangle of diagnosis this film takes as our lot

does not.

…and yet, all those awards and

nominations…

Something in us wants to believe in

the new story of sick people this movie can't figure out how to tell. And that's

terrifying.

Caitlin's Review of Silver Linings Playbook

Like a Lead Balloon

by Caitlin Murphy

A few years back, the Best Picture Oscar

category was expanded from a list of 5 nominations to a maximum of 10. The change seemed to have merit: create room for the less conventionally epic,

the more comedically inclined, the smaller budgeted – or otherwise just somehow humbler – cinematic offerings

to enter the fray. It’s a move that’s

allowed the Oscars to embrace such gems as this year’s Beasts of the Southern Wild, which might otherwise have fallen off

the radar. But it’s also a move that’s

backfired, letting in riff-raff like Silver

Linings Playbook. Written and directed

by David O. Russell (The Fighter) and based on the novel by Matthew Quick, the

film is a warmed-over rom-com that manages mediocrity at every turn.

Set in Philadelphia, the film opens

with Pat Solatono (Bradley Cooper) being released from a mental health

institution where he’s been staying since a breakdown 8 months ago. He comes home to live with his football-obsessed

father (Robert DeNiro) and snack-making mother (Jackie Weaver), armed with a

new determination to always find life’s silver linings (why haven’t other

bi-polar sufferers come up with this yet?). Pat strategizes to re-establish his life,

regain his job, and win back his wife (currently holding a restraining order

against him). Out for a run one day, he

meets Tiffany, a sultry, recently-widowed 20-something, who’s been

self-medicating with sexual promiscuity.

In exchange for getting Tiffany to hand-deliver a letter to his wife (not

sure why the American postal service wouldn’t work), Pat agrees to be Tiffany’s

partner for a dance competition. And thus

the bumpy wheels of the ‘romantic’ plot are put into crunchy motion.

In the vein of As Good as It Gets, the film attempts that awkward blend of actual mental

illness (as opposed to mere personality quirk) with light romantic comedy,

trotting out that old chestnut that true love can fix any noggin. It seems the only recent revision to this rom-com

narrative of “fucked up guy, meets redeeming girl who saves him from himself” is

“fucked up guy, meets similarly fucked up

girl, who saves him from himself.” Equality

at last.

Pat’s behaviour though never quite

feels ugly or complicated enough to do service to the reality of serious mental illness. His capacity for violence is typically tied

to ethical outrage: his initial

breakdown, for instance, resulted from discovering that his wife was having an

affair and losing it on his romantic rival.

Well, who wouldn’t do that, right?

At least a bit. And once he’s out

in the real world again, the only time Pat’s violent rage re-surfaces is when

he defends his Indian therapist from a bunch of racist football fans. Awww.

Focusing also on Pat’s father’s OCD-like

behaviour surrounding his beloved football, as well as his own history of

violence (he’s banned from stadium games), the film seems interested in

suggesting that we’ve all got our own case of the ‘crazies’ and some are just

more official than others. But it’s a

theme that never really gathers much momentum, and limply lies on the ground by

film’s end.

To return to the Oscar noms, the film

also somehow wound up in the undeservedly distinguished company of films like A Streetcar Named Desire and Who’s Afraid of

Virignia Woolf with nominations in all four acting categories (leading and

supporting). Bradley

Cooper, (who no matter what he does in his career I will always comfortably

reduce to ‘that guy from The Hangover’)

demonstrates precisely why he’s always expressing red-carpet bafflement to have

found himself with an acting career. His

performance is so much fluff. As for

Jennifer Lawrence, I like her – her

husky voice, solid build, no-nonsense posture, Juliette Lewis-like snark. She had me at Winter’s Bone and it will take quite a bit to undo that love at

first sight. But she’s wasted here. One-note and predictable.

When Pat’s father loses a huge football

bet that he wagered based on a rabbit’s foot faith in Pat, everyone rallies

around to help him. What follows is a

long, sloppy scene in which the players plot out an elaborate parlay bet to win

back his money by pairing up the results of a football game with those of Pat

and Tiffany’s dance competition. The

scene was reminiscent of a bunch of squabbling screenwriters sitting around

past midnight trying desperately to figure out how to ‘end this thing.’ And this is exactly what the film felt like

far too often – watching what the filmmakers were ‘trying’ to do, the awkward plot-making

machine churning away.

And the bow that ultimately wraps up

this turd? A boy-girl chase scene that

ends with a kiss in the middle of the street.

Of course. Like every other

moment in Silver Linings Playbook, it’s

precisely something you’ve seen before, or else something that vaguely stinks

of it. The entire film lacks texture and

specificity, and when it does manage to scrounge some up, the results are so

contrived and self-conscious, that it might as well have crept back to its

sleepy den of cliché.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)